Fri Apr 2, 2:34 pm ET

(This report is the first in a series on the shutdown of the space shuttle program.)

TITUSVILLE, Fla. — They call it Space City, U.S.A.

Drive along Highway 50 into Titusville, just across the Indian River from NASA's Kennedy Space Center, and you’ll pass a Space Shuttle Inn, Shuttle Car Wash, and Space Coast Pawn & Jewelry. One of the town's two high schools is called Astronaut High. There's an elementary school called Apollo.

Shuttle technician Dan Quinn can't go shopping at the local Walmart without running into co-workers from Kennedy, by far the town's largest employer. His kids used to play a game: Guess how many friends Dad's going to see. Five? Six? Quinn would buy the winner a candy bar.

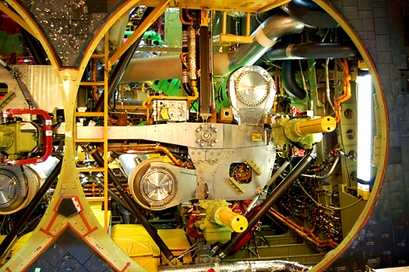

Shuttle technician Dan Quinn stands in front of the engine of the space shuttle Atlantis. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Shuttle technician Dan Quinn stands in front of the engine of the space shuttle Atlantis. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla. Like Hollywood and the movies, Detroit and its cars, Titusville's fortunes have long been tied to aerospace. Prospering during the Apollo heyday, declining when the program was halted. Expanding with the shuttle program, taking a hit with the disasters of Challenger and Columbia.

Now, as NASA prepares to ground its shuttle fleet permanently — just four more launches are planned, including one early Monday — Titusville's 45,000 residents are left to wonder what's next.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were when the Apollo spaceflight program reached its height, putting men on the moon. More than 24,000 people moved to Titusville, eager to work at the new Kennedy Space Center and help the country win the space race.

Quinn's dad, an electrical engineer, was part of the team that built Apollo's lunar module. The family lived in New Mexico at the time, but "my father always brought us out to Kennedy for the open houses and to see the launch area," said Quinn, 56. They watched every blastoff together. It seemed then that the whole nation's — the whole world's — eyes were fixed on the cosmos. That sense of collective awe helped inspire him to follow his father into aerospace, ultimately moving to Titusville to work at Kennedy Space Center more than two decades ago.

Reusable tiles are seen on Atlantis. Over 24,000 tiles, each 6 inches square with individual serial numbers, are hand-glued to the shuttle. The darker tiles are new, and the green tape indicates a tile that needs to be reviewed. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Reusable tiles are seen on Atlantis. Over 24,000 tiles, each 6 inches square with individual serial numbers, are hand-glued to the shuttle. The darker tiles are new, and the green tape indicates a tile that needs to be reviewed. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.But Titusville suffered when Apollo's missions to the moon abruptly ended in 1972. The town's growth, once exponential, ground to a halt. Al Koller, a longtime resident (Titusville High class of 1959) and an electrical engineer for NASA during the Apollo boom, remembers the program shutdown as an abrupt reversal of fortune locally.

"Friends would become enemies because they were laid off and I wasn't," said Koller, who retired from NASA in 1992. "Neighbors on either side of me were in the process of bailing out of their homes because they couldn't afford to remain here after they were laid off. Close to the end, you could buy almost any kind of house for no money down."

And then the space shuttle program rode to the rescue. It wasn't Apollo — Titusville experienced a sharp decline in tourism after that golden era — but it rekindled excitement.

Marcia Gaedke moved to Titusville when she was 2, at the tail end of the Apollo era — too young to remember the city's economic descent. What she remembers is that shuttle launches became "a part of life" when the first orbiter, Columbia, went up on April 12, 1981.

Workers attend to space shuttle Atlantis. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Workers attend to space shuttle Atlantis. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla."Growing up in Titusville, I hardly knew anyone who didn’t have some sort of connection to Kennedy Space Center," said Gaedke, now president of the city's Chamber of Commerce. "Everyone had a mom, uncle, cousin who worked there."

The program brought its share of visitors, too — sometimes in the tens of thousands — vying for the best launch vantage point at places like Space View Park.

But when the space shuttle Challenger exploded while departing from Earth in 1986, and Columbia broke apart upon its return in 2003, the town despaired. After each disaster, the shuttle program experienced years-long hiatuses for the ensuing investigations. The influx of tourists — and the income of the businesses that depended on them — dwindled.

And the pain wasn't just economic but deeply personal.

"Losing those seven [Columbia] astronauts was like losing my brothers and sisters," said Dan Quinn, who has six siblings, two of them retired aerospace workers. At the time of the 2003 disaster, he'd been working on the shuttles' thermal protection system.

Atlantis in a hangar. The whole shuttle fleet is scheduled to be retired this year. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Atlantis in a hangar. The whole shuttle fleet is scheduled to be retired this year. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.Early the next year, President George W. Bush announced that the aging shuttle fleet would be mothballed in 2010. Taking its place would be a new program, Constellation, to send astronauts back to the moon by 2020 and onward to Mars.

The news may not have spelled the end, but it was still a blow to the town. "To people like me, who have grown up with the shuttle program, its retirement is like losing a family member," Gaedke said.

The hope around Titusville and Kennedy Space Center was that most of the 8,000 NASA shuttle contract workers would simply flow into corresponding positions in the Constellation program. But preliminary projections two years ago found that Kennedy could lose as much as 80 percent of its contract workforce, about 6,400 jobs.

As if that wasn't bad enough, this year Obama revealed a 2011 budget with no money allocated for Constellation, effectively canceling Bush’s plan and instead recommending that the focus be on privatized spaceflight. Though Congress still has to OK the measure, Titusville faces the possibility of another economic upheaval.

A closer look at a shuttle engine. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

A closer look at a shuttle engine. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla."It’s like déjà vu," an echo of President Nixon axing the Apollo mission, Koller said. "We have a lot of frightened people here, not ready to end their careers. They don't know what in the world they are going to do."

Yes, Koller said, it's true that Titusville isn't as dependent on aerospace as it was in the '70s — the shuttle workforce is half the size of Apollo's, and the city is about twice as big now — but thousands still depend on the space industry. “I’d say the situation is actually worse now," he said, "because the economy is flat. ’72 and ’73 wasn’t that great either, but it wasn’t like this. People could at least go and find a new job."

The town's contraction has already begun. Since Bush's announcement of the shuttles' retirement, enrollment at Astronaut High School — built in 1962 to accommodate the Apollo boom — is down more than a third, Principal Terry Humphrey said.

"There’s lots of people with long faces here," he said. "A lot of the folks who knew the end [of the shuttle program] was coming left. And the students that remain are concerned that their parents won’t have paying jobs soon." The city's other high school is also on the decline, and five of the city's six elementary schools are now eligible for federal assistance because they have such large low-income populations.

Reusable heat shields, part of the shuttle thermal protection system, are seen in a hangar. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Reusable heat shields, part of the shuttle thermal protection system, are seen in a hangar. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla."About 25 percent of the students have direct ties to the space center, but when you add those who are tied indirectly — the people who support the space program, the construction workers, local businesses, food providers, et cetera — the number goes up a whole lot," Humphrey said. "We’re all somehow connected to the space center; it’s what drives our economy."

It's also central to the town’s pride. What kind of future is in store for Space City, U.S.A., with the shuttle program shutting down and nothing to fill its vacuum? Will it be a commercial center for spaceflight? And if aerospace does become a largely private endeavor, will companies want to move operations elsewhere?

The space industry is "so much a part of our heritage and history," said Gaedke, the Chamber of Commerce president. She hasn't given up. "Hopefully we’ll fight tooth and nail for it to stay in Titusville."

Quinn is trying to stay positive too. "I'm hoping we’ll have another program to go to. If not, well, you know, we'll just cross that bridge when we come to it. Right now, my whole team’s just focused on flying out the last few missions, proving our abilities to get men safely into space."

The inside of a shuttle heat shield. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

The inside of a shuttle heat shield. Photographed at Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Fla.Koller, who has lived most of his life in Titusville and is now an advisor to aerospace students at community colleges, has the next generation in mind. He tells them to be flexible about their career ambitions and to remember that their skills are transferrable: "For instance, if you can be a good aerospace technician, you can be a skilled medical technician."

But like Quinn, the NASA retiree is a second-generation "rocket rat" — his dad was an aerospace worker, too — and space is in his blood. He can't imagine leaving this home, a place from which so many people have blasted off for the great unknown.

"I found my little piece of heaven."

No comments:

Post a Comment